Optimizers in deep learning

February 28, 2024 14 min read

In this post I briefly describe the concepts beside the most popular optimizer algorithms in deep learning. I cover SGD, RMSprop, AdaGrad, Adam, AdamW, AMSGrad etc.

Given a loss function , neural networks aim to find its (ideally global, in practice - local) minimum, attained at some parameters vector .

In all iterative methods we are going to start from some initialization of parameters and make steps of size in a certain search direction : .

The way we define search direction and step size differs significantly between methods.

First order method: Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

A simple way to implement this minimization from practical standpoint is to consider Taylor expansion of :

,

where is the gradient of loss function, calculated over the whole set of samples .

The simplest optimizer, based on first-order approximation, is known as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD).

In SGD the search direction ideally corresponds to neg-gradient direction: .

In practice we approximate true gradient using , calculated over a mini-batch of samples as an approximation of true gradient.

This leads to the following method:

, where is learning rate.

Second order methods: Newton-Raphson method and quasi-newtonian methods

In case of first-order methods the search direction

Second order methods are based on Newton-Raphson formula. Consider Taylor approximation of loss function up to the second term:

, where is Hessian matrix. Equivalently:

Again, substitute the whole dataset with mini-batches , so that .

Find the direction that minimizes by taking a derivative in of second-order Taylor approximation:

Hence, and .

In practice full calculation of Hessian at each step of the algorithm is computationally expensive. A whole set of methods, known as quasi-newtonian, stem from the idea of computationally-effective approximation of Hessian or inverse Hessian. The simplest way to achieve that is to approximate just the diagonal of Hessian with difference of consecutive gradients computations. Such an approximation was suggested by LeCun in 1988, and a mixture of this approach with AdaGrad was suggested by his team in 2012.

Natural Gradient Descent (NGD)

TODO: Fisher information matrix is negative Hessian of log-likelihood.

TODO: Fisher information matrix is the Hessian of KL-divergence between distributions and

TODO: natural gradient is the direction of steepest descent in distribution space

Adaptive learning rate gradient methods

A whole different class of methods stems from the idea that for some batches, and some parts of landscape the gradient would be huge in absolute value, while in some points it would be small.

With that in mind, we cannot choose one learning rate step to rule them all. We need it to be adaptable to the absolute value of gradient.

Momentum and Nesterov Adaptive Gradient

Very soon it was found out quite soon that keeping the learning rate the same leads to very slow training.

Hence, momentum-based methods appeared, which added an extra momentum term to the weight updates:

, where the last term represents momentum.

Alternatively one might denote momentum as and represent momentum method as follows:

and

In 1983 Yuri Nesterov suggested Nesterov Accelerate Gradients method, which is similar to momentum method, but with an alteration:

, where and .

They say that Nesterov momentum looks ahead into future and uses momentum to predict it.

Rprop

The 1992 algorithm Rprop was one of the early optimizers with this notion in mind. It used to work for batches of size 1, i.e. for purely stochastic gradient descent, not mini-batch stochastic gradient descent.

Ideology of this algorithm is as follows: consider a coordinate of gradient. If over two consecutive iterations this coordinate has the same sign, we increase the step size in this coordinate by some value. If the signs are different, we decrease the step size.

AdaGrad

AdaGrad was suggested in 2011 and sparked a series of copycats methods with tiny adjustments, such as RMSprop, AdaDelta and Adam.

It adapts the step size differently than Rprop or momentum algorithms.

During the calculation of gradients AdaGrad maintains the history of outer products of gradients:

In practice this matrix of outer products is never used and just its diagonal (which represents second moments of gradients) is maintained:

Finally, we apply this matrix to gradients to maintain some momentum in each coordinate:

RMSprop

For some reason classical Rprop does not work for mini-batches.

Hence, in his 2012 lecture Hinton came up with a modification of Rprop, called RMSprop, adapted for mini-batch stochastic optimization.

Actually, RMSprop is much closer to AdaGrad than to Rprop with the difference that it uses exponential moving average (EMA) instead of aggregation of second moment of gradient over the whole history. I guess, an observation that is simple moving average (SMA) works, EMA usually works better, was an inspiration for this method.

During the calculation of gradients RMSprop maintains moving averages of squares of gradients:

He uses it to divide gradient by its square root (or, equivalently, multiply by a square root of its inverse):

Here instead of altering the effective learning rate by hand like in Rprop, we just accumulate EMA of gradient squares and divide by it.

There’s a hint of a quasi-newtonian vibe to this method, if were a diagonal approximation of Hamiltonian, but I cannot see, how to give such an interpretation to it.

AdaDelta

Matt Zeiler came up with this method in late 2012, drawing inspiration from AdaGrad.

He kept the EMA of second moment of gradient in denominator as in RMSprop (not sure about who came up with this earlier, he or Hinton). This term reminded him of diagonal approximation of Hessian from quasi-newtonian method, too.

But also he came up with a notion that metaphoric units, in which is measured, should be the same as , which is not the case with AdaGrad and others, while it is in case of quasi-newtonian methods, as , where is dimensionless, while is measured in some units (e.g. meters, kilograms etc.). Thus, in quasi-newtonian methods and dimensionality is maintained, so that , so that if i-th coordinate of is in meters, its update is also in meters.

This is not the case for AdaGrad, where update of i-th coordinate is dimension-less. Hence, Zeiler suggests to use EMA in numerator as well for gradient updates themselves to maintain dimensionality:

, where

is accumulated second moment of gradient and

is accumulated squared update of theta.

Adam

Adam is a 2014 improvement over AdaGrad and RMSprop. It is actually very similar to AdaDelta, except by the fact that they use linear accumulated gradient instead of square updates of theta:

, where

is accumulated second moment of gradient and

is accumulated gradient (I am slightly vague and omit normalization of both numerator and denominator here by (1 - \beta) here; obviously betas for numerator and denominator can be different).

There’s an interesting discussion of interaction of ADAM with Fisher information matrix, natural gradient and quasi-newtonian methods.

TODO: Connection to Hessian, natural gradient and Fisher information.

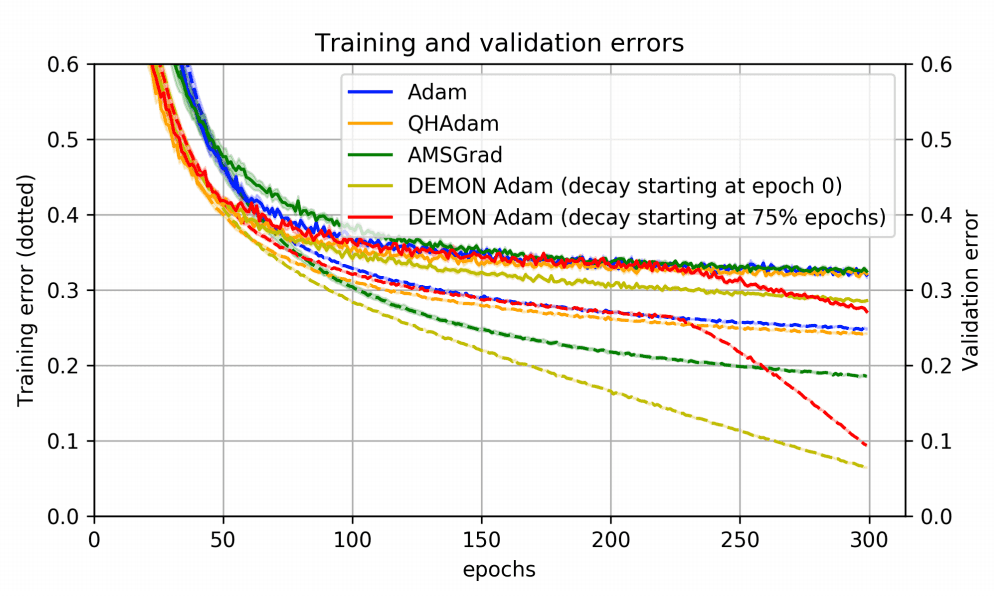

AMSGrad

AMSGrad is a 2018 modification of Adam by Reddi et al. Those authors find out that sometimes Adam fails to converge and, thus, slightly changed its formulation. It is almost exactly the same, except by the fact they are using maximum of current step’s and previou step’s second momentum:

, where

is accumulated second moment of gradient and

is accumulated gradient.

AdamW and Adam-l2

AdamW is 2019 modification of Adam.

Oftentimes Adam optimizer is combined with l2-regularization of weights, so that instead of minimizing they minimize .

From here one can come up with different construction of Adam-like optimizer. Naive one, called Adam-l2 works as follows:

is the analogue of gradient, which includes l2-normalization;

, is the update rule, analogous to Adam, where as usual:

is accumulated second moment of gradient and

is accumulated gradient.

An alternative to it is called AdamW and stems from a different problem statement:

- here we keep gradient the same, but add regularization term to the Adam update rule

, note the last term, corresponding to regularization; the others are as usual:

is accumulated second moment of gradient and

is accumulated gradient.

These two alternative views at regularization stem from the same approach, but lead to somewhat different performance.

References:

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/298623 - Rprop paper (1992)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XhZahXzEuNo - Hinton lecture 6 on RMSprop

- https://towardsdatascience.com/understanding-rmsprop-faster-neural-network-learning-62e116fcf29a - a post on deriving RMSprop from Rprop and/or AdaGrad

- https://optimization.cbe.cornell.edu/index.php?title=AdaGrad - Cornell page on AdaGrad

- https://www.jmlr.org/papers/volume12/duchi11a/duchi11a.pdf - AdaGrad paper

- https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~brecht/cs294docs/week1/03.Zinkevich.pdf - online learning paper by M.Zinkevich (2003)

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1212.5701.pdf - AdaDelta paper (late 2012)

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1412.6980.pdf - ADAM paper (2014)

- https://medium.com/konvergen/adaptive-method-based-on-exponential-moving-averages-with-guaranteed-convergence-amsgrad-and-89d337c821cb - medium post by Roan Gylberth on AMSGrad, AdaGrad and Adam.

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.05101.pdf - AdamW paper (2019)

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.00089.pdf - a good digest of AdamW vs Adam-l2 (2022)

- https://education.yandex.ru/handbook/ml/article/optimizaciya-v-ml - a nice post from Yandex education

- https://agustinus.kristia.de/techblog/2018/03/11/fisher-information/ - on Fisher information matrix and its connection to Hessian of log-likelihood

- https://agustinus.kristia.de/techblog/2018/03/14/natural-gradient/ - on Natural Gradient Descent

Written by Boris Burkov who lives in Moscow, Russia, loves to take part in development of cutting-edge technologies, reflects on how the world works and admires the giants of the past. You can follow me in Telegram