Divergence, Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem and Laplacian

September 20, 2021 9 min read

Laplacian is an interesting object that initially was invented in multivariate calculus and field theory, but its generalizations arise in multiple areas of applied mathematics, from computer vision to spectral graph theory and from differential geometry to homologies. In this post I am going to explain the intuition behind Laplacian, which requires the introduction of the notion of divergence first. I'll also touch the famous Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem.

In the late XVIII - early XIX centuries great mathematicians, such as Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Carl Friedrich Gauss and others were laying the foundations of modern physics. One of the most notable problems, they were studying, was heat transfer. The mathematical methods, developed in order to solve it, such as multivariate calculus and Fourier analysis are invaluable and are now ubiquitous in applied mathematics.

Throughout this post I will be using examples from heat transfer and diffusion problems as a motivation to explain the intuition behind mathematical concepts.

In order to introduce the concept of Laplacian, I have to introduce the notion of divergence first, as Laplacian is its special case. After we have dealt with divergence, the properties of Laplacian will become obvious.

Divergence

The notion of divergence in multivariate calculus has 2 very different definitions: conceptual and technical.

Their equivalence is not trivial to see, and I’ll dedicate a whole separate section below to prove it.

Conceptual definition

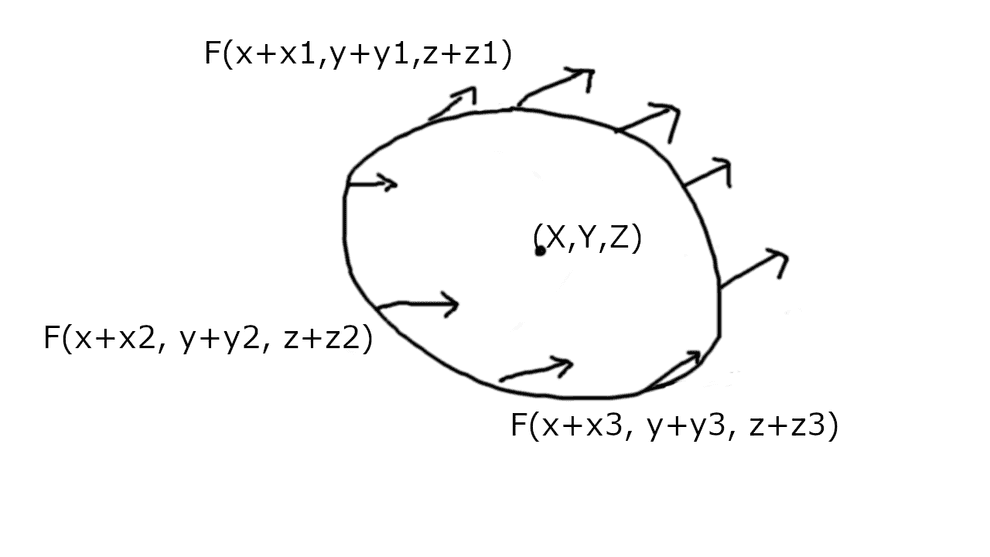

Conceptually, divergence of a vector field at some point is the integral of flow of that vector field over an infinitesimal closed contour with area and volume around that point.

Technical definition

Technically, divergence of a vector field is a sum of its partial derivatives of the vector field coordinates: .

Note that is a vector field, not a scalar field. So, divergence is not just a dot product of gradient by (1,1,1) vector, as the notation abuse might suggest.

Proof of equivalence of conceptual and technical definitions

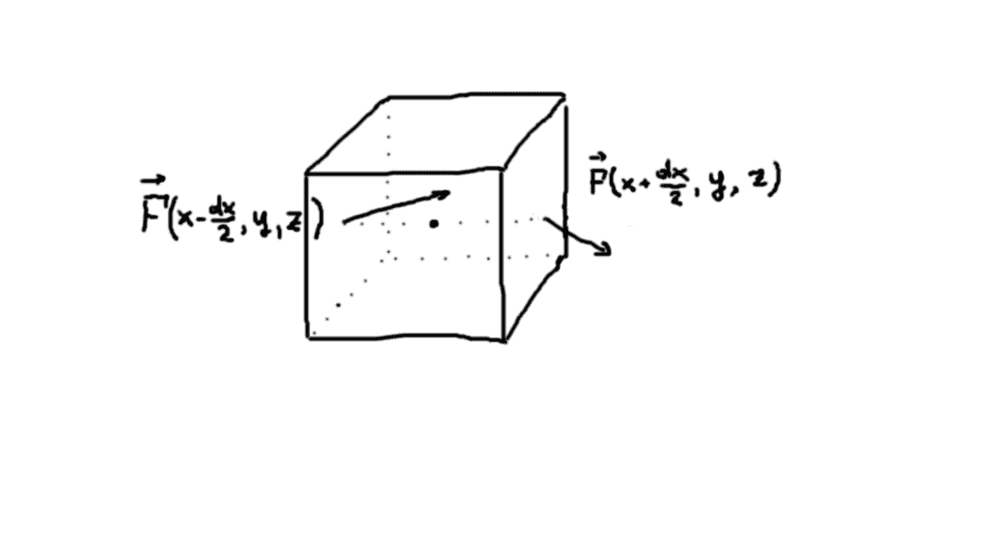

Say, our infinitesimal surface, surrounding the given point is a cube, with edges aligned with the coordinate vectors, so that edge of length is parallel to axis, is parallel to axis and is parallel to axis.

As cube is small, we can assume the flow over each of its faces equal to the area of that face, multiplied by flow through its center.

Divergence, according to conceptual definition, would be the total flow through all 6 faces of the cube. I will denote a part of total divergence, corresponding to the flow through the pair of faces, orthogonal to the axis , as . Thus, the total divergence equals .

Let us calculate the divergence through the two faces, orthogonal to axis:

So, the total divergence is:

We see that conceptual definition converged to the technical definition.

Invariance of divergence to coordinate change

We chose our infinitesimal cube so, that its edges are aligned in parallel to the coordinate axes.

However, divergence would not change, if we chose the directions differently.

Indeed, note that divergence is the trace of Jacobian matrix, and trace is invariant to similarity transformations (such as rotation of coordinates).

To show this fact, first show that by direct calculation and from this it follows that .

Why this works for non-rectangular surfaces?

TODO

Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem

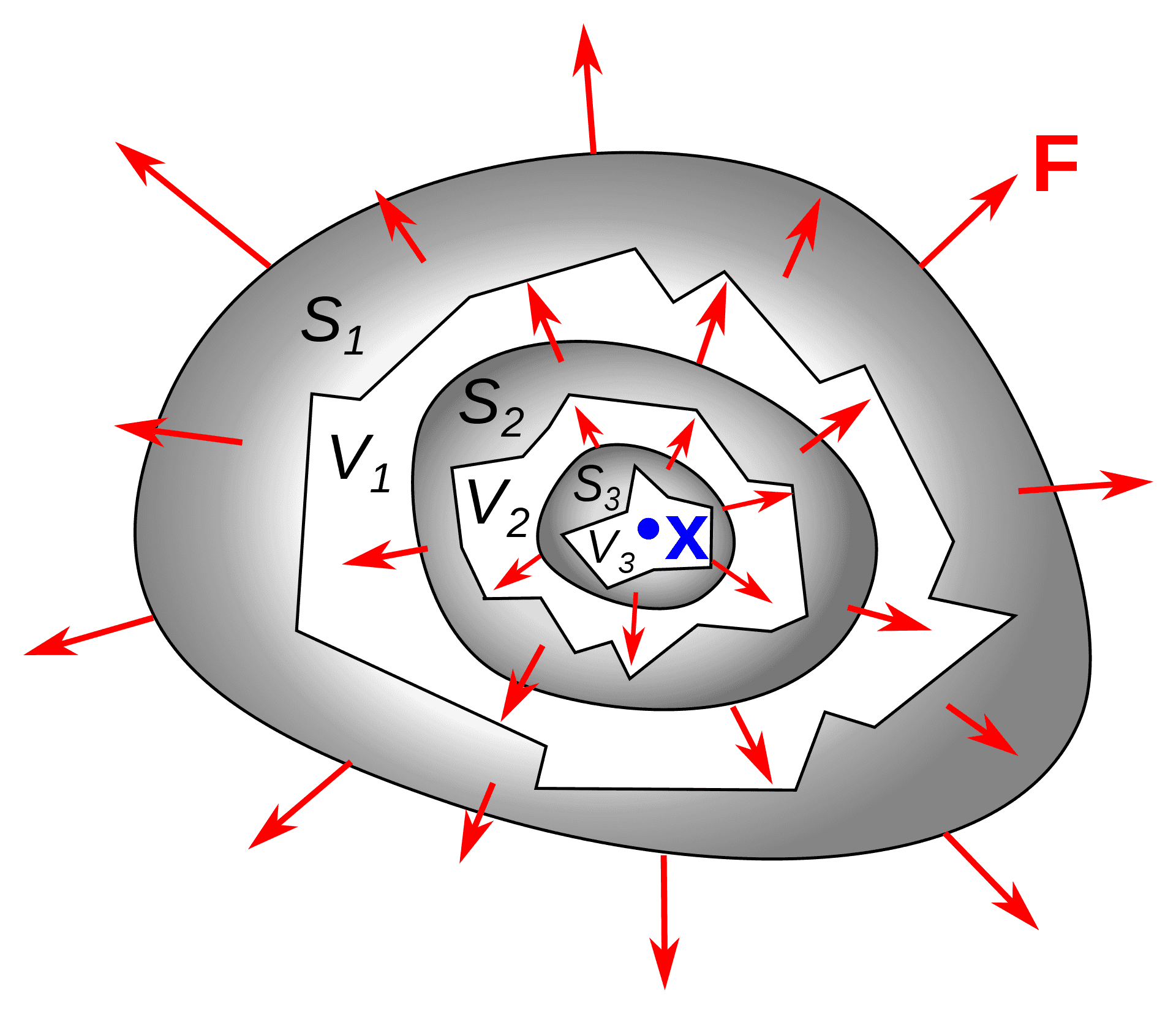

Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem basically states that you can calculate flow of the vector field through a macroscopic closed surface as an integral of divergence over the volume, confined in that surface.

It is proved by application of same discussion, as we employed for infinitesimal surface/volume (just split the whole macroscopic volume into these infinitesimal pieces).

Laplacian

Laplacian follows from divergence in one simple step.

Suppose that instead of a vector fields you have a scalar field . For instance, instead of flow of matter, you have a distribution of temperature or concentration over a volume.

Well, we can get a vector field out of that scalar field easily: just find the gradient of the scalar field and use it as the vector field.

The operator is called Laplacian.

Being a divergence, Laplacian is invariant to the change of basis as well (by the way, it is the trace of Hessian).

Laplacian as a measure of non-conformness of a point

For Laplacian there exists an alternative interpretation: you can draw an infinitesimal sphere around the point and calculate the average value of a function over that sphere. The difference between the average value and the value at the point corresponds to Laplacian:

If a point is very much different from its neighbourhood, Laplacian will be great. If it is exactly the same as its surroundings, Laplacian will be 0.

Proof of equivalence of definition of Laplacian and its interpretation as a measure of non-conformness

By Taylor series:

By symmetry components with linear parts cancel out: , etc.

Components with quadratic parts stay, but compound:

Substitute this into:

.

Applications outside multivariate calculus and field theory

There are several discrete analogues of the continuous Laplacian that are used in various fields of computer science.

Discrete Laplace operator in computer vision for edge detection

Discrete version of Laplace operator is a convolutional filter, used in computer vision for edge detection. In 2D case it is a 3-by-3 matrix of the following structure:

Try applying it to a black-and-white photo of a brick wall. You will see that every pixel of a brick will become black after application of Laplace operator as a convolutional filter (because neighbors of this pixel from all directions have the same color). But the edges of a brick will become white, because pixels outside have a different color.

Discrete Laplacian in spectral graph theory

This is a subject of a whole separate post on spectral graph theory.

References

- https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/2451248/why-divergence-only-cares-about-partial-derivative-of-x-y-z-respectively - helpful answer on divergence intuition

- https://isis2.cc.oberlin.edu/physics/dstyer/Electrodynamics/Laplacian.pdf - a good paper on why Laplacian corresponds to the difference between point and its neighbors

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L9hU4xrhEDs - a great video from Quantum Mechanics series on meaning of Laplacian in Hamiltonian, its correpsondence to momentum etc.

Written by Boris Burkov who lives in Moscow, Russia, loves to take part in development of cutting-edge technologies, reflects on how the world works and admires the giants of the past. You can follow me in Telegram